Contact Tracing and COVID-19: Lessons From HIV

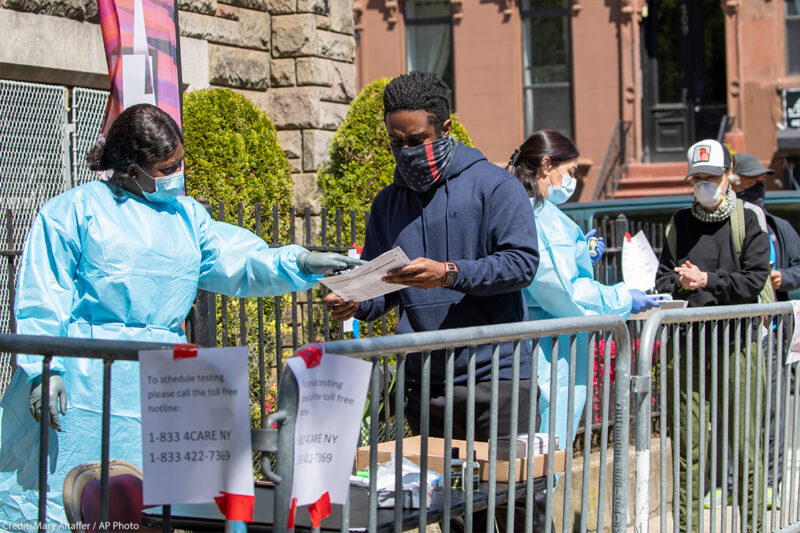

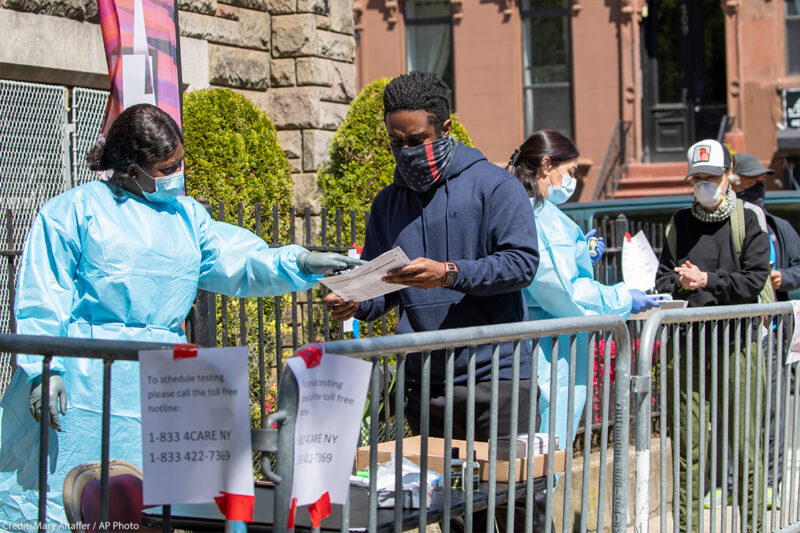

As we enter the next phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, attention is turning to contact tracing. States and cities are gearing up to hire thousands of people to help identify and notify those who may have been exposed to the virus, in an effort to help reduce rates of transmission and keep the virus from growing exponentially within a community. The hope is that expanded testing will allow health departments to identify those who have the virus, and then reach out to anyone those people have been in close contact with and encourage those individuals to self-quarantine and get tested.

We are that our state health departments know how to do this, as it has been used with other communicable diseases, including HIV. While some comparisons being drawn between HIV and COVID-19 are often , there are important things to learn from the public health response to HIV that should guide the implementation of widespread contact tracing for COVID-19.

Contact tracing requires at least two key things to succeed: People must be willing to provide this information, and people must be able to act on it. To make that possible, health and contact information must be protected from unnecessary disclosure. We must also ensure that anyone who is required to self-isolate as a result of contact tracing has the resources to do so, and that criminalization never enters the picture. It is folly to expect anyone to identify close contacts if the consequence will be that they are ordered to stay home, in some cases leaving them with no way to support themselves and their loved ones. It is even less likely people will share information if it could expose themselves, their friends, or family to risk of arrest.

There are some major differences between HIV and COVID-19 that bear on the relative balance of civil liberties and public health interests inherent to assessing any public health response. HIV is not spread through casual contact, whereas COVID-19 is. And unlike HIV, there are currently no treatments for COVID-19 that reduce viral load to the point that people cannot transmit the disease. That means the universe of potential contacts is much greater with respect to COVID-19. On the other hand, COVID-19 seems to have a relatively short incubation period – which means that only contacts from within a several week window of time after a person tests positive are relevant.

There are also some important similarities: Both viruses can be spread by people who are asymptomatic and do not know their status. Both viruses are having a more devastating impact on already marginalized communities, including of . And with both epidemics, we have seen and , and egregious in of public health restrictions by police.

With those caveats, here are some critical lessons we can draw from our response to HIV:

Contact tracing is one tool, not a solution.

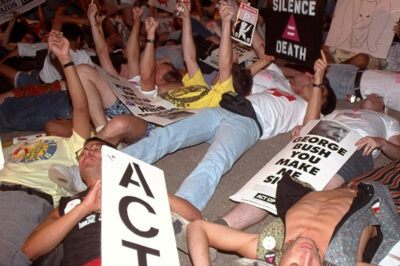

We should not have unrealistic expectations for contact tracing. Despite a long-standing program of partner notification for people diagnosed with HIV, new HIV transmission continues to occur. Ending HIV stigma and ensuring access to health care for all have proven vital for effective HIV prevention. Contact tracing may be one component of effective prevention for COVID-19, but we must not lose sight of other important aspects of responding to the crisis.

Maintaining trust is vital.

To be effective, contact tracing and notifications require trust. To build enough trust for people to provide information about all contacts of more than 10-15 minutes over the past two weeks, we must give them clear information about what information will be collected, how it will be kept secure, how it will be used, and what resources will be provided to anyone ordered to self-quarantine. Without trust, not only will people be less likely to share their contacts, but they will also be less likely to seek testing in the first place and to follow other recommendations from public health officials.

To that end, contact tracing information must only be used for public health purposes, and clear restrictions must be put in place so it cannot be used by law enforcement, including for immigration purposes. Without those restrictions, already vulnerable communities may be less likely to provide information about their contacts, thereby exacerbating inequality by increasing infection rates within those communities.

Privacy and anonymity must be protected.

We must ensure the privacy and anonymity of people who test positive for COVID-19 is protected as much as possible during notifications. This means that when people are told they may have been in contact with someone with COVID-19 and should self-quarantine, they should receive only the information they really need. We want to avoid situations where individuals with COVID-19 are blamed for the ensuing restrictions on others’ liberty that may follow their positive test. That is partly why nobody should be coerced into participating in a contact tracing effort.

When people are told to self-isolate or quarantine, they must receive the resources they need to support themselves and their families, without risk of losing their jobs, housing, or health insurance. They also must have access to COVID-19 testing, and health care if they need it.

We will also need to work to protect the security of all data collected through both in-person contact tracing and any technology-based tracing. Again, we can learn from experiences with HIV, where we know that data breaches happen as a result of both malice and human error.

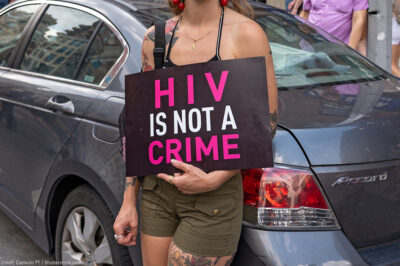

Criminalization is never the answer.

One of the most important lessons from HIV is that we must not rely on the to solve this epidemic. Nearly all states have enacted laws that made exposing another to HIV a crime. Some criminalize conduct with no risk of transmission, like spitting. And most of these laws don’t consider intent or actual risk. These laws are still on the books today. They have upended lives and have not stopped the epidemic. In fact, a Louisiana man was reportedly charged with a felony for allegedly trying to spit on a police officer while living with HIV, even though we have known for decades that HIV cannot be transmitted through saliva.

Criminalization does not stop HIV. Instead, it deters people from testing, it increases risk, and it falls most heavily on the people who are already more heavily policed, including people of color, immigrants, people who engage in sex work, LGBTQ people, and more. Incarceration itself also worsens people’s health and interferes with prevention. For COVID-19, the of expanding incarceration are especially disastrous.

Any restrictions must be based on the best available evidence and regularly reevaluated.

Finally, any restrictions imposed in conjunction with contact tracing or follow up to diagnosis need to be based on best available evidence, and only as restrictive as is necessary. They should be re-evaluated as our understanding of the virus grows, and treatment and testing options change. We know that sometimes those restrictions can be more burdensome than necessary, inequitable, and may perpetuate stigma, shame, and blame.

Contact tracing may offer promise. But for it to have any chance of success, it must be implemented in a way that is just and equitable and does not exacerbate existing inequalities.